4 Cardinal Signs Tmd

Signs Of TMD. Signs that you may have a TMD problem include: Teeth Clenching and Grinding (Bruxism) Clenching and grinding of the teeth (bruxism) is a common sign of TMJ disorder. The clenching and grinding of the teeth put additional stress on already tired, overworked muscles and can result in pain being referred to the head, neck, face. Do You Know and Possess These 4 Cardinal Signs of Wellness Wellness is not merely the absence of burnout. Nor is engagement the soul defining quality of wellness.

| Temporomandibular joint dysfunction | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Temporomandibular joint dysfunction syndrome, temporomandibular disorder, others[1] |

| Temporomandibular joint | |

| Specialty | Oral medicine |

Temporomandibular joint dysfunction (TMD, TMJD) is an umbrella term covering pain and dysfunction of the muscles of mastication (the muscles that move the jaw) and the temporomandibular joints (the joints which connect the mandible to the skull). The most important feature is pain, followed by restricted mandibular movement,[2] and noises from the temporomandibular joints (TMJ) during jaw movement. Although TMD is not life-threatening, it can be detrimental to quality of life,[3] because the symptoms can become chronic and difficult to manage.

TMD is a symptom complex rather than a single condition, and it is thought to be caused by multiple factors.[4][5] However, these factors are poorly understood,[6] and there is disagreement as to their relative importance. There are many treatments available,[7] although there is a general lack of evidence for any treatment in TMD, and no widely accepted treatment protocol. Common treatments include provision of occlusal splints, psychosocial interventions like cognitive behavioral therapy, physical therapy, and pain medication or others. Most sources agree that no irreversible treatment should be carried out for TMD.[8]

About 20% to 30% of the adult population are affected to some degree.[7] Usually people affected by TMD are between 20 and 40 years of age,[3] and it is more common in females than males.[9] TMD is the second most frequent cause of orofacial pain after dental pain (i.e. toothache).[10]

- 1Classification

- 3Causes

- 4Pathophysiology

- 4.1Anatomy and physiology

- 4.2Mechanisms of main signs and symptoms

- 4.2.2Pain

- 5Diagnosis

- 5.2Diagnostic Imaging in TMD

- 6Management

- 6.7Alternative medicine

Classification[edit]

|

TMD is considered by some to be one of the 4 major symptom complexes in chronic orofacial pain, along with burning mouth syndrome, atypical facial pain and atypical odontalgia.[12] TMD has been considered as a type of musculoskeletal,[13]neuromuscular,[14] or rheumatological disorder.[13] It has also been called a functional pain syndrome,[6] and a psychogenic disorder.[15] Others consider TMD a 'central sensitivity syndrome', in reference to evidence that TMD might be caused by a centrally mediated sensitivity to pain.[16] It is hypothesized that there is a great deal of similarity between TMD and other pain syndromes like fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, interstitial cystitis, headache, chronic lower back pain and chronic neck pain. These disorders have also been theorized to be caused by centrally mediated sensitivity to pain, and furthermore they often occur together.[16]

Definitions and terminology[edit]

Frequently, TMD has been treated as a single syndrome, but the prevailing modern view is that TMD is a cluster of related disorders with many common features.[13] Indeed, some have suggested that in the future the term TMD may be discarded as the different causes are fully identified and separated into different conditions.[15] Sometimes, 'temporomandibular joint dysfunction' is described as the most common form of temporomandibular disorder,[4] whereas many other sources use the term temporomandibular disorder synonymously, or instead of the term temporomandibular joint dysfunction. In turn, the term temporomandibular disorder is described as 'a clinical term [referring to] musculoskeletal disorders affecting the temporomandibular joints and their associated musculature. It is a collective term which represents a diverse group of pathologies involving the temporomandibular joint, the muscles of mastication, or both'.[2] Another definition of temporomandibular disorders is 'a group of conditions with similar signs and symptoms that affect the temporomandibular joints, the muscles of mastication, or both.'[17] Temporomandibular disorder is a term that creates confusion since it refers to a group of similarly symptomatic conditions, whilst many sources use the term temporomandibular disorders as a vague description rather than a specific syndrome, and refer to any condition which may affect the temporomandibular joints (see table). The temporomandibular joint is susceptible to a huge range of diseases, some rarer than others, and there is no implication that all of these will cause any symptoms or limitation in function at all.

The preferred terms in medical publications is to an extent influenced by geographic location, e.g. in the United Kingdom, the term 'pain dysfunction syndrome' is in common use, and in other countries different terms are used.[4] In the United States, the term 'temporomandibular disorder' is generally favored. The American Academy of Orofacial Pain uses temporomandibular disorder, whilst the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research uses temporomandibular joint disorder.[18] A more complete list of synonyms for this topic is extensive, with some being more commonly used than others. In addition to those already mentioned, examples include 'temporomandibular joint pain dysfunction syndrome', 'temporomandibular pain dysfunction syndrome', 'temporomandibular joint syndrome', 'temporomandibular dysfunction syndrome', 'temporomandibular dysfunction', 'temporomandibular disorder', 'temporomandibular syndrome', 'facial arthromyalgia', 'myofacial pain dysfunction syndrome', 'craniomandibular dysfunction' (CMD), 'myofacial pain dysfunction', 'masticatory myalgia', 'mandibular dysfunction', and 'Costen's syndrome'.

The lack of standardization in terms is not restricted to medical papers. Notable internationally recognized sources vary in both their preferred term, and their offered definition, e.g.

'Temporomandibular Pain and Dysfunction Syndrome – Aching in the muscles of mastication, sometimes with an occasional brief severe pain on chewing, often associated with restricted jaw movement and clicking or popping sounds.' (Classification of Chronic Pain, International Association for the Study of Pain).[19]

'Headache or facial pain attributed to temporomandibular joint disorder.' (International Classification of Headache Disorders 2nd edition (ICHD-2), International Headache Society).[20]

'Temporomandibular joint-pain-dysfunction syndrome' listed in turn under 'Temporomandibular joint disorders' (International Classification of Diseases 10th revision, World Health Organization).[21]

In this article, the term temporomandibular disorder is taken to mean any disorder that affects the temporomandibular joint, and temporomandibular joint dysfunction (here also abbreviated to TMD) is taken to mean symptomatic (e.g. pain, limitation of movement, clicking) dysfunction of the temporomandibular joint, however there is no single, globally accepted term or definition[18] concerning this topic.

By cause and symptoms[edit]

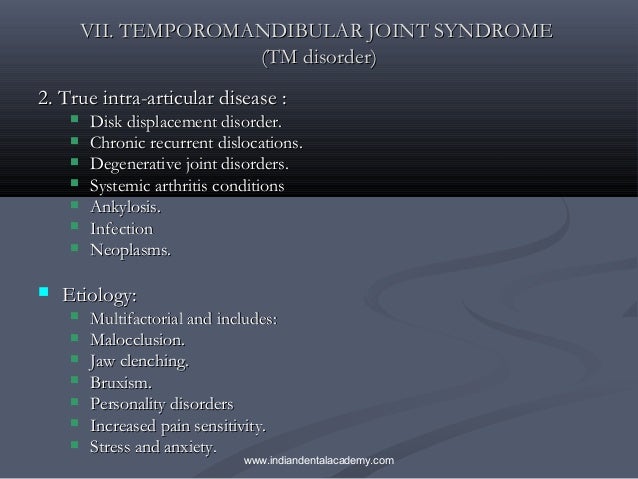

It has been suggested that TMD may develop following physical trauma, particularly whiplash injury, although the evidence for this is not conclusive. This type of TMD is sometimes termed 'posttraumatic TMD' (pTMD) to distinguish it from TMD of unknown cause, sometimes termed 'idiopathic TMD' (iTMD).[13] Sometimes muscle-related (myogenous) TMD (also termed myogenous TMD, or TMD secondary to myofascial pain and dysfunction) is distinguished from joint-related TMD (also termed arthogenous TMD, or TMD secondary to true articular disease), based upon whether the muscles of mastication or the TMJs themselves are predominantly involved. This classification, which effectively divides TMD into 2 syndromes, is followed by the American Academy of Orofacial Pain.[18] However, since most people with TMD could be placed into both of these groups, which makes a single diagnosis difficult when this classification is used. The Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC/TMD) allows for multiple diagnoses in an attempt to overcome the problems with other classifications. RDC/TMD considers temporomandibular disorders in 2 axes; axis I is the physical aspects, and axis II involves assessment of psychological status, mandibular function and TMD-related psychosocial disability.[18] Axis I is further divided into 3 general groups. Group I are muscle disorders, group II are disc displacements and group III are joint disorders,[10] although it is common for people with TMD to fit into more than one of these groups.

By duration[edit]

Sometimes distinction is made between acute TMD, where symptoms last for less than 3 months, and chronic TMD, where symptoms last for more than 3 months.[2] Not much is known about acute TMD since these individuals do not typically attend in secondary care (hospital).[2]

Signs and symptoms[edit]

Signs and symptoms of temporomandibular joint disorder vary in their presentation. The symptoms will usually involve more than one of the various components of the masticatory system, muscles, nerves, tendons, ligaments, bones, connective tissue, or the teeth.[22] TMJ dysfunction is commonly associated with symptoms affecting cervical spine dysfunction and altered head and cervical spine posture.[23]

The three classically described, cardinal signs and symptoms of TMD are:[10][24]

- Pain and tenderness on palpation in the muscles of mastication, or of the joint itself (preauricular pain – pain felt just in front of the ear). Pain is the defining feature of TMD and is usually aggravated by manipulation or function,[2] such as when chewing, clenching,[11] or yawning, and is often worse upon waking. The character of the pain is usually dull or aching, poorly localized,[6] and intermittent, although it can sometimes be constant. The pain is more usually unilateral (located on one side) rather than bilateral.[19] It is rarely severe.[25]

- Limited range of mandibular movement,[2] which may cause difficulty eating or even talking. There may be locking of the jaw, or stiffness in the jaw muscles and the joints, especially present upon waking.[17] There may also be incoordination, asymmetry or deviation of mandibular movement.[2]

- Noises from the joint during mandibular movement, which may be intermittent.[4] Joint noises may be described as clicking,[2] popping,[19] or crepitus (grating).[17]

Other signs and symptoms have also been described, although these are less common and less significant than the cardinal signs and symptoms listed above. Examples include:

- Headache (possibly),[4] e.g. pain in the occipital region (the back of the head), or the forehead;[11] or other types of facial pain including migraine,[22]tension headache.[22] or myofascial pain.[22]

- Pain elsewhere, such as the teeth[11] or neck.[9]

- Diminished auditory acuity (hearing loss).[22]

- Tinnitus (occasionally).[17]

- Dizziness.[9]

- Sensation of malocclusion (feeling that the teeth do not meet together properly).[19]

Causes[edit]

TMD is a symptom complex (i.e. a group of symptoms occurring together and characterizing a particular disease), which is thought to be caused by multiple, poorly understood factors,[4][5][6] but the exact etiology is unknown.[26] There are factors which appear to predispose to TMD (genetic, hormonal, anatomical), factors which may precipitate it (trauma, occlusal changes, parafunction), and also factors which may prolong it (stress and again parafunction).[17] Overall, two hypotheses have dominated research into the causes of TMD, namely a psychosocial model and a theory of occlusal dysharmony.[26] Interest in occlusal factors as a causative factor in TMD was especially widespread in the past, and the theory has since fallen out of favor and become controversial due to lack of evidence.

Disc displacement[edit]

In people with TMD, it has been shown that the lower head of lateral pterygoid contracts during mouth closing (when it should relax), and is often tender to palpation. To theorize upon this observation, some have suggested that due to a tear in the back of the joint capsule, the articular disc may be displaced forwards (anterior disc displacement), stopping the upper head of lateral pterygoid from acting to stabilize the disc as it would do normally. As a biologic compensatory mechanism, the lower head tries to fill this role, hence the abnormal muscle activity during mouth closure. There is some evidence that anterior disc displacement is present in proportion of TMD cases. Anterior disc displacement with reduction refers to abnormal forward movement of the disc during opening which reduces upon closing. Anterior disc displacement without reduction refers to an abnormal forward, bunched-up position of the articular disc which does not reduce. In this latter scenario, the disc is not intermediary between the condyle and the articular fossa as it should be, and hence the articular surfaces of the bones themselves are exposed to a greater degree of wear (which may predispose to osteoarthritis in later life).[5]

Degenerative joint disease[edit]

The general term 'degenerative joint disease' refers to arthritis (both osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis) and arthrosis. The term arthrosis may cause confusion since in the specialized TMD literature it means something slightly different from in the wider medical literature. In medicine generally, arthrosis can be a nonspecific term for a joint, any disease of a joint (or specifically degenerative joint disease), and is also used as a synonym for osteoarthritis.[27] In the specialized literature that has evolved around TMD research, arthrosis is differentiated from arthritis by the presence of low and no inflammation respectively.[6] Both are however equally degenerative.[6] The TMJs are sometimes described as one of the most used joints in the body. Over time, either with normal use or with parafunctional use of the joint, wear and degeneration can occur, termed osteoarthritis. Rheumatoid arthritis, an autoimmune joint disease, can also affect the TMJs. Degenerative joint diseases may lead to defects in the shape of the tissues of the joint, limitation of function (e.g. restricted mandibular movements), and joint pain.[6]

Psychosocial factors[edit]

Emotional stress (anxiety, depression, anger) may increase pain by causing autonomic, visceral and skeletal activity and by reduced inhibition via the descending pathways of the limbic system. The interactions of these biological systems have been described as a vicious 'anxiety-pain-tension' cycle which is thought to be frequently involved in TMD. Put simply, stress and anxiety cause grinding of teeth and sustained muscular contraction in the face. This produces pain which causes further anxiety which in turn causes prolonged muscular spasm at trigger points, vasoconstriction, ischemia and release of pain mediators. The pain discourages use of the masticatory system (a similar phenomenon in other chronic pain conditions is termed 'fear avoidance' behavior), which leads to reduced muscle flexibility, tone, strength and endurance. This manifests as limited mouth opening and a sensation that the teeth are not fitting properly.[12]

Persons with TMD have a higher prevalence of psychological disorders than people without TMD.[28] People with TMD have been shown to have higher levels of anxiety, depression, somatization and sleep deprivation, and these could be considered important risk factors for the development of TMD.[5][28] In the 6 months before the onset, 50–70% of people with TMD report experiencing stressful life events (e.g. involving work, money, health or relationship loss). It has been postulated that such events induce anxiety and cause increased jaw muscle activity. Muscular hyperactivity has also been shown in people with TMD whilst taking examinations or watching horror films.[5]

Others argue that a link between muscular hyperactivity and TMD has not been convincingly demonstrated, and that emotional distress may be more of a consequence of pain rather than a cause.[26]

Bruxism[edit]

Bruxism is an oral parafunctional activity where there is excessive clenching and grinding of the teeth. It can occur during sleep or whilst awake. The cause of bruxism itself is not completely understood, but psychosocial factors appear to be implicated in awake bruxism and dopaminergic dysfunction and other central nervous system mechanisms may be involved in sleep bruxism. If TMD pain and limitation of mandibular movement are greatest upon waking, and then slowly resolve throughout the day, this may indicate sleep bruxism. Conversely, awake bruxism tends to cause symptoms that slowly get worse throughout the day, and there may be no pain at all upon waking.

The relationship of bruxism with TMD is debated. Many suggest that sleep bruxism can be a causative or contributory factor to pain symptoms in TMD.[5][26][29][30] Indeed, the symptoms of TMD overlap with those of bruxism.[31] Others suggest that there is no strong association between TMD and bruxism.[25] A systematic review investigating the possible relationship concluded that when self-reported bruxism is used to diagnose bruxism, there is a positive association with TMD pain, and when more strict diagnostic criteria for bruxism are used, the association with TMD symptoms is much lower.[32] Self-reported bruxism is probably a poor method of identifying bruxism.[30] There are also very many people who grind their teeth and who do not develop TMD.[17] Bruxism and other parafunctional activities may play a role in perpetuating symptoms in some cases.[33]

Other parafunctional habits such as pen chewing, lip and cheek biting (which may manifest as morsicatio buccarum or linea alba), are also suggested to contribute to the development of TMD.[5] Other parafunctional activities might include jaw thrusting, excessive gum chewing, nail biting and eating very hard foods.

Trauma[edit]

Trauma, both micro and macrotrauma, is sometimes identified as a possible cause of TMD; however, the evidence for this is not strong.[25] Prolonged mouth opening (hyper-extension) is also suggested as a possible cause. It is thought that this leads to microtrauma and subsequent muscular hyperactivity. This may occur during dental treatment, with oral intubation whilst under a general anesthetic, during singing or wind instrument practice (really these can be thought of as parafunctional activities).[5] Damage may be incurred during violent yawning, laughing, road traffic accidents, sports injuries, interpersonal violence, or during dental treatment,[25] (such as tooth extraction).[5]

It has been proposed that a link exists between whiplash injuries (sudden neck hyper-extension usually occurring in road traffic accidents), and the development of TMD. This has been termed 'post-traumatic TMD', to separate it from 'idiopathic TMD'.[13] Despite multiple studies having been performed over the years, the cumulative evidence has been described as conflicting, with moderate evidence that TMD can occasionally follow whiplash injury.[13] The research that suggests a link appears to demonstrate a low to moderate incidence of TMD following whiplash injury, and that pTMD has a poorer response to treatment than TMD which has not developed in relation to trauma.[13]

Occlusal factors[edit]

Occlusal factors as an etiologic factor in TMD is a controversial topic.[5] Abnormalities of occlusion (problems with the bite) are often blamed for TMD but there is no evidence that these factors are involved.[25] Occlusal abnormalities are incredibly common, and most people with occlusal abnormalities do not have TMD.[34] Although occlusal features may affect observed electrical activity in masticatory muscles,[35] there are no statistically significant differences in the number of occlusal abnormalities in people with TMD and in people without TMD.[5] There is also no evidence for a causal link between orthodontic treatment and TMD.[5] The modern, mainstream view is that the vast majority of people with TMD, occlusal factors are not related.[17] Theories of occlusal factors in TMD are largely of historical interest. A causal relationship between occlusal factors and TMD was championed by Ramfjord in the 1960s.[15] A small minority of dentists continue to prescribe occlusal adjustments in the belief that this will prevent or treat TMD despite the existence of systematic reviews of the subject which state that there is no evidence for such practices,[36] and the vast majority of opinion being that no irreversible treatment should be carried out in TMD (see Occlusal adjustment).

Genetic factors[edit]

TMD does not obviously run in families like a genetic disease. It has been suggested that a genetic predisposition for developing TMD (and chronic pain syndromes generally) could exist. This has been postulated to be explained by variations of the gene which codes for the enzyme catechol-O-methyl transferase (COMT) which may produce 3 different phenotypes with regards pain sensitivity. COMT (together with monoamine oxidase) is involved in breaking down catecholamines (e.g. dopamine, epinephrine, and norepinephrine). The variation of the COMT gene which produces less of this enzyme is associated with a high sensitivity to pain. Females with this variation, are at 2–3 times greater risk of developing TMD than females without this variant. However this theory is controversial since there is conflicting evidence.[6]

Hormonal factors[edit]

Since females are more often affected by TMD than males, the female sex hormoneestrogen has been suggested to be involved.[6] The results of one study suggested that the periods of highest pain in TMD can be correlated with rapid periods of change in the circulating estrogen level. Low estrogen was also correlated to higher pain.[15] In the menstrual cycle, estrogen levels fluctuate rapidly during ovulation, and also rapidly increases just before menstruation and rapidly decreases during menstruation. Post-menopausal females who are treated with hormone replacement therapy are more likely to develop TMD, or may experience an exacerbation if they already had TMD. Several possible mechanisms by which estrogen might be involved in TMD symptoms have been proposed. Estrogen may play a role in modulating joint inflammation, nociceptive neurons in the trigeminal nerve, muscle reflexes to pain and μ-opioid receptors.[6]

Possible associations[edit]

TMD has been suggested to be associated with other conditions or factors, with varying degrees evidence and some more commonly than others. E.g. It has been shown that 75% of people with TMD could also be diagnosed with fibromyalgia, since they met the diagnostic criteria, and that conversely, 18% of people with fibromyalgia met diagnostic criteria for TMD.[16] A possible link between many of these chronic pain conditions has been hypothesized to be due to shared pathophysiological mechanisms, and they have been collectively termed 'central sensitivity syndromes',[16] although other apparent associations cannot be explained in this manner. Recently a plethora of research has substantiated a causal relationship between TMD and Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA). Severe TMD restricts oral airway opening, and can result in a retrognathic posture that results in glossal blockage of the oropharynx as the tongue relaxes in sleep. This mechanism is exacerbated by alcohol consumption, as well as other chemicals that result in reduced myotonic status of the oropharynx.

- Obstructive sleep apnea.[37][38]

- Rheumatoid arthritis.[17]

- Systemic joint laxity.[17]

- Chronic back pain.[15]

- Irritable bowel syndrome.[16]

- Headache.[16]

- Chronic neck pain.[16]

- Interstitial cystitis.[16]

- Regular scuba diving.[5][39]

Pathophysiology[edit]

Anatomy and physiology[edit]

Temporomandibular joints[edit]

The temporomandibular joints are the dual articulation of the mandible with the skull. Each TMJ is classed as a 'ginglymoarthrodial' joint since it is both a ginglymus (hinging joint) and an arthrodial (sliding) joint,[40] and involves the condylar process of the mandible below, and the articular fossa (or glenoid fossa) of the temporal bone above. Between these articular surfaces is the articular disc (or meniscus), which is a biconcave, transversely oval disc composed of dense fibrous connective tissue. Each TMJ is covered by a fibrous capsule. There are tight fibers connecting the mandible to the disc, and loose fibers which connect the disc to the temporal bone, meaning there are in effect 2 joint capsules, creating an upper joint space and a lower joint space, with the articular disc in between. The synovial membrane of the TMJ lines the inside of the fibrous capsule apart from the articular surfaces and the disc. This membrane secretes synovial fluid, which is both a lubricant to fill the joint spaces, and a means to convey nutrients to the tissues inside the joint. Behind the disc is loose vascular tissue termed the 'bilaminar region' which serves as a posterior attachment for the disc and also fills with blood to fill the space created when the head of the condyle translates down the articular eminence.[41] Due to its concave shape, sometimes the articular disc is described as having an anterior band, intermediate zone and a posterior band.[42] When the mouth is opened, the initial movement of the mandibular condyle is rotational, and this involves mainly the lower joint space, and when the mouth is opened further, the movement of the condyle is translational, involving mainly the upper joint space.[43] This translation movement is achieved by the condylar head sliding down the articular eminence, which constitutes the front border of the articular fossa.[34] The function of the articular eminence is to limit the forwards movement of the condyle.[34] The ligament directly associated with the TMJ is the temporomandibular ligament, also termed the lateral ligament, which really is a thickening of the lateral aspect of the fibrous capsule.[34] The stylomandibular ligament and the sphenomandibular ligament are not directly associated with the joint capsule. Together, these ligaments act to restrict the extreme movements of the joint.[44]

Muscles of mastication[edit]

The muscles of mastication are paired on each side and work together to produce the movements of the mandible. The main muscles involved are the masseter, temporalis and medial and lateral pterygoid muscles.

They can be thought of in terms of the directions they move the mandible, with most being involved in more than one type of movement due to the variation in the orientation of muscle fibers within some of these muscles.

- Protrusion – Lateral and medial pterygoid.

- Retraction – Posterior fibers of temporalis (and the digastric and geniohyoid muscles to a lesser extent).

- Elevation – Anterior and middle fibers of temporalis, the superficial and deep fibers of masseter and the medial pterygoid.[41]

- Lateral movements – Medial and lateral pterygoid (the ipsilateral temporalis and the pterygoid muscles of the contralateral side pull the mandible to the ipsilateral side).[34]

Each lateral pterygoid muscle is composed of 2 heads, the upper or superior head and the lower or inferior head. The lower head originates from the lateral surface of the lateral pterygoid plate and inserts at a depression on the neck of mandibular condyle, just below the articular surface, termed the pterygoid fovea. The upper head originates from the infratemporal surface and the infratemporal crest of the greater wing of the sphenoid bone. The upper head also inserts at the fovea, but a part may be attached directly to the joint capsule and to the anterior and medial borders of the articular disc.[41] The 2 parts of lateral pterygoid have different actions. The lower head contracts during mouth opening, and the upper head contracts during mouth closing. The function of the lower head is to steady the articular disc as it moves back with the condyle into the articular fossa. It is relaxed during mouth closure.[5]

Mechanisms of main signs and symptoms[edit]

Joint noises[edit]

Noises from the TMJs are a symptom of dysfunction of these joints. The sounds commonly produced by TMD are usually described as a 'click' or a 'pop' when a single sound is heard and as 'crepitation' or 'crepitus' when there are multiple, grating, rough sounds. Most joint sounds are due to internal derangement of the joint, which is a term used to describe instability or abnormal position of the articular disc.[45] Clicking often accompanies either jaw opening or closing, and usually occurs towards the end of the movement. The noise indicates that the articular disc has suddenly moved to and from a temporarily displaced position (disk displacement with reduction) to allow completion of a phase of movement of the mandible.[5][26] If the disc displaces and does not reduce (move back into position) this may be associated with locking. Clicking alone is not diagnostic of TMD since it is present in high proportion of the general population, mostly in people who have no pain.[5] Crepitus often indicates arthritic changes in the joint, and may occur at any time during mandibular movement, especially lateral movements.[5] Perforation of the disc may also cause crepitus.[34] Due to the proximity of the TMJ to the ear canal, joint noises are perceived to be much louder to the individual than to others. Often people with TMD are surprised that what sounds to them like very loud noises cannot be heard at all by others next to them. However, it is occasionally possible for loud joint noises to be easily heard by others in some cases and this can be a source of embarrassment e.g. when eating in company.

Pain[edit]

Pain symptoms in TMD can be thought of as originating from the joint (arthralgia), or from the muscles (myofascial), or both. There is a poor correlation between TMD pain severity and evidence of tissue pathology.[6]

Arthralgia[edit]

Generally, degenerative joint changes are associated with greater pain.

Myofascial pain[edit]

Pain originating from the muscles of mastication as a result of abnormal muscular function or hyperactivity. The muscular pain is frequently, but not always, associated with daytime clenching or nocturnal bruxism.[46]

Referred TMD pain[edit]

Sometimes TMD pain can radiate or be referred from its cause (i.e. the TMJ or the muscles of mastication) and be felt as headaches, earache or toothache.[11]

Due to the proximity of the ear to the temporomandibular joint, TMJ pain can often be confused with ear pain.[22] The pain may be referred in around half of all patients and experienced as otalgia (earache).[47] Conversely, TMD is an important possible cause of secondary otalgia. Treatment of TMD may then significantly reduce symptoms of otalgia and tinnitus, as well as atypical facial pain.[48] Despite some of these findings, some researchers question whether TMJD therapy can reduce symptoms in the ear, and there is currently an ongoing debate to settle the controversy.[22]

Limitation of mandibular movement[edit]

The jaw deviates to the affected side during opening,[19] and restricted mouth opening usually signifies that both TMJs are involved, but severe trismus rarely occurs. If the greatest reduction in movement occurs upon waking then this may indicate that there is concomitant sleep bruxism. In other cases the limitation in movement gets worse throughout the day.[5]

The jaw may lock entirely.[5]

Limitation of mandibular movement itself may lead to further problems involving the TMJs and the muscles of mastication. Changes in the synovial membrane may lead to a reduction in lubrication of the joint and contribute to degenerative joint changes.[49] The muscles become weak, and fibrosis may occur. All these factors may lead to a further limitation of jaw movement and increase in pain.[49]

Degenerative joint disease, such as osteoarthritis or organic degeneration of the articular surfaces, recurrent fibrous or bony ankylosis, developmental abnormality, or pathologic lesions within the TMJ. Myofascial pain syndrome.[medical citation needed]

Diagnosis[edit]

Group I: muscle disorders Ia. Myofascial pain:

Ib. Myofascial pain with limited opening:

Group II: disc displacements IIa. Disc displacement with reduction:

IIb. Disc displacement without reduction with limited opening:

IIc. Disc displacement without reduction, without limited opening:

Group III: arthralgia, osteoarthritis, osteoarthrosis IIIa. Arthralgia:

IIIb. Osteoarthritis of the TMJ:

IIIc. Osteoarthrosis of the TMJ:

|

Pain is the most common reason for people with TMD to seek medical advice.[2] Joint noises may require auscultation with a stethoscope to detect.[19] Clicks of the joint may also be palpated, over the joint itself in the preauricular region, or via a finger inserted in the external acoustic meatus,[17] which lies directly behind the TMJ.The differential diagnosis is with degenerative joint disease (e.g. osteoarthritis), rheumatoid arthritis, temporal arteritis, otitis media, parotitis, mandibular osteomyelitis, Eagle syndrome, trigeminal neuralgia,[medical citation needed]oromandibular dystonia,[medical citation needed] deafferentation pains, and psychogenic pain.[19]

Diagnostic criteria[edit]

Various diagnostic systems have been described. Some consider the Research Diagnostic Criteria method the gold standard.[17] Abbreviated to 'RDC/TMD', this was first introduced in 1992 by Dworkin and LeResche in an attempt to classify temporomandibular disorders by etiology and apply universal standards for research into TMD.[51] This method involves 2 diagnostic axes, namely axis I, the physical diagnosis, and axis II, the psychologic diagnosis.[17] Axis I contains 3 different groups which can occur in combinations of 2 or all 3 groups,[17] (see table).

McNeill 1997 described TMD diagnostic criteria as follows:[2]

- Pain in muscles of mastication, the TMJ, or the periauricular area (around the ear), which is usually made worse by manipulation or function.

- Asymmetric mandibular movement with or without clicking.

- Limitation of mandibular movements.

- Pain present for a minimum of 3 months.

The International Headache Society's diagnostic criteria for 'headache or facial pain attributed to temporomandibular joint disorder' is similar to the above:[20]

- A. Recurrent pain in one or more regions of the head or face fulfilling criteria C and D

- B. X-ray, MRI or bone scintigraphy demonstrate TMJ disorder

- C. Evidence that pain can be attributed to the TMJ disorder, based on at least one of the following:

- pain is precipitated by jaw movements or chewing of hard or tough food

- reduced range of or irregular jaw opening

- noise from one or both TMJs during jaw movements

- tenderness of the joint capsule(s) of one or both TMJs

- D. Headache resolves within 3 months, and does not recur, after successful treatment of the TMJ disorder

Diagnostic Imaging in TMD[edit]

The advantages brought about by diagnostic imaging mainly lie within diagnosing TMD of articular origin. Additional benefits of imaging the TMJ are as follows:[52]

- Assess the integrity of anatomical structures in suspicion of disorders

- Staging the extent of any pathology

- Monitoring and staging the progress of disease

- Determining the effects of treatment

When clinical examination alone is unable to bring sufficient detail to ascertain the state of the TMJ, imaging methods can act as an adjuvant to clinical examination in the diagnosis of TMD.[52]

Plain radiography[edit]

This method of imaging allows the visualisation of the joint’s mineralised areas, therefore excluding the cartilage and soft tissues.[52] A disadvantage of plain radiography is that images are prone to superimposition from surrounding anatomical structures, thereby complicating radiographic interpretation.[52] It was concluded that there is no evidence to support the use of plain radiography in the diagnosis of joint erosions and osteophytes.[53] It is reasonable to conclude that plain film can only be used to diagnose extensive lesions.[53]

Panoramic tomography[edit]

The distortion brought about by panoramic imaging decreases its overall reliability. Data concluded from a systematic review showed that only extensive erosions and large osteophytes can be detected by panoramic imaging.[53]

Computerised tomography (CT)[edit]

Studies have shown that tomography of the TMJ provided supplementary information that supersedes what is obtainable from clinical examination alone.[54] However, the issues lies in the fact that it is impossible to determine whether certain patient groups would benefit more or less from a radiographic examination.[55]

The main indications of CT and CBCT examinations are to assess the bony components of the TMJ, specifically the location and extent of any abnormalities present.[56][57][58]

The introduction of cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) imaging allowed a lower radiation dose to patients, in comparison to conventional CT. Hintze et al compared CBCT and CT techniques and their ability to detect morphological TMJ changes. No significant difference was concluded in terms of their diagnostic accuracy.[59]

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)[edit]

MRI is the optimal choice for the imaging of soft tissues surrounding the TMJ.[60][57] It allows three-dimensional evaluation of the axial, coronal and sagittal plane.[56] It is the gold standard method for assessing disc position and is sensitive for intra-articular degenerative alterations.[60]

Indications for MRI are pre-auricular pain, detection of joint clicking and crepitus, frequent incidents of subluxation and jaw dislocation, limited mouth opening with terminal stiffness, suspicion of neoplastic growth, and osteoarthritic symptoms.[61][62] It is also useful for assessing the integrity of neural tissues, which may produce orofacial pain when compressed.[61]

MRI provides evaluation of pathology such as necrosis and oedema all without any exposure to ionizing radiation.[61] However, there is a high cost associated with this method of imaging, due to the need for sophisticated facilities.[56] Caution should be taken in patient selection, as MRI is contraindicated in those with claustrophobic tendencies, pacemakers and metallic heart valves, ferromagnetic foreign bodies and pregnant women.[62]

Ultrasound[edit]

Where internal TMJ disorders are concerned, ultrasound (US) imaging can be a useful alternative in assessing the position of the disc[63][64] While having significant diagnostic sensitivity, US has inadequate specificity when identifying osteoarthrosis. Moreover, it is not accurate enough for the diagnosis of cortical and articular disc morphology based on the findings done related to morphological alterations.[65] However, with US, identification of effusion in individuals with inflammatory conditions associated with pain is possible and confirmed by MRI [64][65][57]

US can be a useful alternative in initial investigation of internal TMJ dysfunctions especially in MRI contraindicated individuals[56] despite its limitations.[62][64] in addition to being less costly,[57] US provides a quick and comfortable real-time imaging without exposing the individual to ionizing radiation[63][64][65]

US is commonly assessed in the differential diagnosis of alterations of glandular and neighbouring structures, such as the TMJ and the masseter muscle. Symptoms of sialendenitis and sialothiasis cases can be confused with Eagle syndrome, TMD, myofascial and nerve pain, and other pain of the orofacial region.[56]

US assessment is also indicated where there is need to identify the correct position of the joint spaces for infiltrative procedures, arthrocentesis, and viscosupplementation. This is due to the fact that US provides a dynamic and real-time location of the component of the joints, while providing adequate lubrication and washing, which can be confirmed by the joint space increase post-treatment.[66]

In Android Studio, click Tools SDKManager. Windows drivers for all other devices are providedby the respective hardware manufacturer, as listed in thedocument.Note:If you're developing on Mac OS X or Linux, then you do not need to install a USBdriver. The Google USB Driver is required for Windows if you want to performdebugging with any ofthe Google Nexus devices. Driver dispositivo usb mtp download. Or, get it from theas follows:. Instead see.You can download the Google USB Driver for Windows in one of two ways:.Click here to download the Google USB Driver ZIP file(ZIP).

Management[edit]

TMD can be difficult to manage, and since the disorder transcends the boundaries between several health-care disciplines — in particular, dentistry and neurology, the treatment may often involve multiple approaches and be multidisciplinary.[44] Most who are involved in treating and, researching TMD now agree that any treatment carried out should not permanently alter the jaw or teeth, and should be reversible.[8][14] To avoid permanent change, over-the-counter or prescription pain medications may be prescribed.[67]

Psychosocial and behavioral interventions[edit]

Given the important role that psychosocial factors appear to play in TMD, psychosocial interventions could be viewed to be central to management of the condition.[28] There is a suggestion that treatment of factors that modulate pain sensitivity such as mood disorders, anxiety and fatigue, may be important in the treatment of TMD, which often tends to attempt to address the pain directly.[28]

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) has been used in TMD and has been shown to be efficacious by meta analyses.[68]

Hypnosis is suggested by some to be appropriate for TMD. Studies have suggested that it may even be more beneficial than occlusal splint therapy, and has comparable effects to relaxation techniques.[28]

Relaxation techniques include progressive muscle relaxation, yoga, and meditation.[28] It has been suggested that TMD involves increased sensitivity to external stimuli leading to an increased sympathetic ('fight or flight') response with cardiovascular and respiratory alterations.[28] Relaxation techniques cause reduced sympathetic activity, including muscle relaxation and reducing sensitivity to external stimuli, and provoke a general sense of well being and reduced anxiety.[28]

Devices[edit]

Occlusal splints (also termed bite plates or intra-oral appliances) are often used by dentists to treat TMD. They are usually made of acrylic and can be hard or soft. They can be designed to fit onto the upper teeth or the lower teeth. They may cover all the teeth in one arch (full coverage splint) or only some (partial coverage splint). Splints are also termed according to their intended mechanism, such as the anterior positioning splint or the stabilization splint.[17] Although occlusal splints are generally considered a reversible treatment,[49] sometimes partial coverage splints lead to pathologic tooth migration (changes in the position of teeth). Normally splints are only worn during sleep, and therefore probably do nothing for people who engage in parafunctional activities during wakefulness rather than during sleep. There is slightly more evidence for the use of occlusal splints in sleep bruxism than in TMD. A splint can also have a diagnostic role if it demonstrates excessive occlusal wear after a period of wearing it each night. This may confirm the presence of sleep bruxism if it was in doubt. Soft splints are occasionally reported to worsen discomfort related to TMD.[17] Specific types of occlusal splint are discussed below.

A stabilization splint is a hard acrylic splint that forces the teeth to meet in an 'ideal' relationship for the muscles of mastication and the TMJs. It is claimed that this technique reduces abnormal muscular activity and promotes 'neuromuscular balance'. A stabilization splint is only intended to be used for about 2–3 months.[4] It is more complicated to construct than other types of splint since a face bow record is required and significantly more skill on the part of the dental technician. This kind of splint should be properly fitted to avoid exacerbating the problem and used for brief periods of time. The use of the splint should be discontinued if it is painful or increases existing pain.[67] A systematic review of all the scientific studies investigating the efficacy of stabilization splints concluded the following:

'On the basis of our analysis we conclude that the literature seems to suggest that there is insufficient evidence either for or against the use of stabilization splint therapy over other active interventions for the treatment of TMD. However, there is weak evidence to suggest that the use of stabilization splints for the treatment of TMD may be beneficial for reducing pain severity, at rest and on palpation, when compared to no treatment'.[4]

Partial coverage splints are recommended by some experts, but they have the potential to cause unwanted tooth movements, which can occasionally be severe. The mechanism of this tooth movement is that the splint effectively holds some teeth out of contact and puts all the force of the bite onto the teeth which the splint covers. This can cause the covered teeth to be intruded, and those that are not covered to over-erupted. I.e. a partial coverage splint can act as a Dahl appliance. Examples of partial coverage splints include the NTI-TSS ('nociceptive trigeminal inhibitor tension suppression system'), which covers the upper front teeth only. Due to the risks involved with long term use, some discourage the use of any type of partial coverage splint.[17]

An anterior positioning splint is a splint that designed to promote an anteriorly displaced disc. It is rarely used.[17] A 2010 review of all the scientific studies carried out to investigate the use of occlusal splints in TMD concluded:

'Hard stabilization appliances, when adjusted properly, have good evidence of modest efficacy in the treatment of TMD pain compared to non-occluding appliances and no treatment. Other types of appliances, including soft stabilization appliances, anterior positioning appliances, and anterior bite appliances, have some RCT evidence of efficacy in reducing TMD pain. However, the potential for adverse events with these appliances is higher and suggests the need for close monitoring in their use.'[69]

Ear canal inserts are also available, but no published peer-reviewed clinical trials have shown them to be useful.

Medication[edit]

Medication is the main method of managing pain in TMD, mostly because there is little if any evidence of the effectiveness of surgical or dental interventions. Many drugs have been used to treat TMD pain, such as analgesics (pain killers), benzodiazepines (e.g. clonazepam, prazepam, diazepam), anticonvulsants (e.g. gabapentin), muscle relaxants (e.g. cyclobenzaprine), and others. Analgesics that have been studied in TMD include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g. piroxicam, diclofenac, naproxen) and cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors (e.g. celecoxib). Topicalmethyl salicylate and topical capsaicin have also been used. Other drugs that have been described for use in TMD include glucosamine hydrochloride/chondroitin sulphate and propranolol. Despite many randomized control trials being conducted on these commonly used medications for TMD a systematic review carried out in 2010 concluded that there was insufficient evidence to support or not to support the use of these drugs in TMD.[2] Low-doses of anti-muscarinictricyclic antidepressants such as amitriptyline,[70] or nortriptyline have also been described.[71] In a subset of people with TMD who are not helped by either noninvasive and invasive treatments, long term use of opiate analgesics has been suggested, although these drugs carry a risk of drug dependence and other side effects.[72] Examples include morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone, tramadol, hydrocodone, and methadone.[72]

Botulinum toxin solution ('Botox') is sometimes used to treat TMD.[73] Injection of botox into the lateral pterygoid muscle has been investigated in multiple randomized control trials, and there is evidence that it is of benefit in TMD.[74] It is theorized that spasm of lateral pterygoid causes anterior disc displacement. Botulinum toxin causes temporary muscular paralysis by inhibiting acetylcholine release at the neuromuscular junction.[26] The effects usually last for a period of months before they wear off. Complications include the creation of a 'fixed' expression due to diffusion of the solution and subsequent involvement of the muscles of facial expression,[74] which lasts until the effects of the botox wear off. Injections of local anesthetic, sometimes combined with steroids, into the muscles (e.g. the temoralis muscle or its tendon) are also sometimes used. Local anesthetics may provide temporary pain relief, and steroids inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokines.[49] Steroids and other medications are sometimes injected directly into the joint (See Intra-articular injections).

Physiotherapy, biofeedback and similar non-invasive measures[edit]

Physiotherapy (physical therapy) is sometimes used as an adjuvant to other methods of treatment in TMD.[75] There are many different approaches described, but exercises aiming to increase the range of mandibular movements are commonly involved.[49] Jaw exercises aim to directly oppose the negative effects of disuse that may occur in TMD, due to pain discouraging people from moving their jaw. After initial instruction, people are able to perform a physical therapy regimen at home. The most simple method is by regular stretching within pain tolerance, using the thumb and a finger in a 'scissor' maneuver. Gentle force is applied until pain of resistance is felt, and then the position is held for several seconds. Commercial devices have been developed to carry out this stretching exercise (e.g. the 'Therabite' appliance). Over time, the amount of mouth opening possible without pain can be gradually increased. A baseline record of the distance at the start of physical therapy (e.g. the number of fingers that can be placed vertically between the upper and lower incisors), can chart any improvement over time.[49]

It has been suggested that massage therapy for TMD improves both the subjective and objective health status.[76] 'Friction massage' uses surface pressure to causes temporary ischemia and subsequent hyperemia in the muscles, and this is hypothesized to inactivate trigger points and disrupt small fibrous adhesions within the muscle that have formed following surgery or muscular shortening due to restricted movement.[49]

Occasionally physiotherapy for TMD may include the use of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), which may override pain by stimulation of superficial nerve fibers and lead to pain reduction which extends after the time where the TENS is being actually being applied, possibly due to release of endorphins. Others recommend the use of ultrasound, theorized to produce tissue heating, alter blood flow and metabolic activity at a level that is deeper than possible with surface heat applications.[49] There is tentative evidence that low level laser therapy may help with pain.[77]

The goals of a PT in reference to treatment of TMD should be to decrease pain, enable muscle relaxation, reduce muscular hyperactivity, and reestablish muscle function and joint mobility. PT treatment is non-invasive and includes self-care management in an environment to create patient responsibility for their own health.[78]

Therapeutic exercise and Manual Therapy (MT) are used to improve strength, coordination and mobility and to reduce pain. Treatment may focus on poor posture, cervical muscle spasms and treatment for referred cervical origin (pain referred from upper levels of the cervical spine) or orofacial pain . MT has been used to restore normal range of motion, promoting circulation, stimulate proprioception, break fibrous adhesions, stimulate synovial fluid production and reduce pain. Exercises and MT are safe and simple interventions that could potentially be beneficial for patients with TMD. No adverse events regarding exercise therapy and manual therapy have been reported.[78]

There have been positive results when using postural exercises and jaw exercises to treat both myogenous (muscular) and arthrogenous (articular) TMJ dysfunction. MT alone or in combination with exercises shows promising effects.[78]

It is necessary that trails be performed isolating the type of exercise and manual techniques to allow a better understanding of the effectiveness of this treatment. Additionally, details of exercise, dosage, and frequency as well as details on manual techniques should be reported to create reproducible results. High quality trails with larger sample sizes are needed.[78]

There is some evidence that some people who use nighttime biofeedback to reduce nighttime clenching experience a reduction in TMD.[79]

Occlusal adjustment[edit]

This is the adjustment or reorganizing of the existing occlusion, carried out in the belief that this will redistribute forces evenly across the dental arches or achieve a more favorable position of the condyles in the fossae, which is purported to lessen tooth wear, bruxism and TMD, but this is controversial. These techniques are sometimes termed 'occlusal rehabilitation' or 'occlusal equilibration'.[30] At its simplest, occlusal adjustment involves selective grinding (with a dental drill) of the enamel of the occlusal surfaces of teeth, with the aim of allowing the upper teeth to fit with the lower teeth in a more harmonious way.[15] However, there is much disagreement between proponents of these techniques on most of the aspects involved, including the indications and the exact goals. Occlusal adjustment can also be very complex, involving orthodontics, restorative dentistry or even orthognathic surgery. Some have criticized these occlusal reorganizations as having no evidence base, and irreversibly damaging the dentition on top of the damage already caused by bruxism.[30] A 'middle ground' view of these techniques is that occlusal adjustment in most cases of TMD is neither desirable nor helpful as a first line treatment, and furthermore, with few exceptions, any adjustments should be reversible.[17] However, most dentists consider this unnecessary overtreatment,[17] with no evidence of benefit.[34] Specifically, orthodontics and orthognathic surgery are not considered by most to be appropriate treatments for TMD.[34] A systematic review investigating all the scientific studies carried out on occlusal adjustments in TMD concluded the following:

'There is an absence of evidence of effectiveness for occlusal adjustment. Based on these data occlusal adjustment cannot be recommended for the treatment or prevention of TMD.[36]

These conclusions were based largely on the fact that, despite many different scientific studies investigating this measure as a therapy, overall no statistically significant differences can be demonstrated between treatment with occlusal adjustment and treatment with placebo. The reviewers also stated that there are ethical implications if occlusal adjustment was found to be ineffective in preventing TMD.[36]

Orthodontic treatment, as described earlier, is sometimes listed as a possible predisposing factor in the development of TMD. On the other hand, orthodontic treatment is also often carried out in the belief that it may treat or prevent TMD. Another systematic review investigating the relationship between orthodontics and TMD concluded the following:

'There is no evidence to support or refute the use of orthodontic treatment for the treatment of TMD. In addition, there are no data which identify a link between active orthodontic intervention and the causation of TMD. Based on the lack of data, orthodontic treatment cannot be recommended for the treatment or prevention of TMD.'[15]

A common scenario where a newly placed dental restoration (e.g. a crown or a filling) is incorrectly contoured, and creates a premature contact in the bite. This may localize all the force of the bite onto one tooth, and cause inflammation of the periodontal ligament and reversible increase in tooth mobility. The tooth may become tender to bite on. Here, the 'occlusal adjustment' has already taken place inadvertently, and the adjustment aims to return to the pre-existing occlusion. This should be distinguished from attempts to deliberately reorganize the native occlusion.

Surgery[edit]

Attempts in the last decade to develop surgical treatments based on MRI and CAT scans now receive less attention. These techniques are reserved for the most difficult cases where other therapeutic modalities have failed. The American Society of Maxillofacial Surgeons recommends a conservative/non-surgical approach first. Only 20% of patients need to proceed to surgery.

Examples of surgical procedures that are used in TMD, some more commonly than others, include arthrocentesis, arthroscopy, meniscectomy, disc repositioning, condylotomy or joint replacement. Invasive surgical procedures in TMD may cause symptoms to worsen.[7] Meniscectomy, also termed discectomy refers to surgical removal of the articular disc. This is rarely carried out in TMD, it may have some benefits for pain, but dysfunction may persist and overall it leads to degeneration or remodeling of the TMJ.[80]

Alternative medicine[edit]

Acupuncture[edit]

Acupuncture is sometimes used for TMD.[44] There is limited evidence that acupuncture is an effective symptomatic treatment for TMD.[81][82][83] A short term reduction in muscular pain of muscular origin can usually be observed after acupuncture in TMD,[83] and this is more than is seen with placebo.[84] There are no reported adverse events of acupuncture when used for TMD,[84] and some suggest that acupuncture is best employed as an adjuvent to other treatments in TMD.[83] However, some suggest that acupuncture may be no more effective than sham acupuncture,[85] that many of the studies investigating acupuncture and TMD suffer from significant risk of bias,[83] and that the long term efficacy of acupuncture for TMD is unknown.[83][84]

Chiropractic[edit]

Chiropractic adjustments (also termed manipulations or mobilizations) are sometimes used in the belief that this will treat TMD.[86] Related conditions that are also claimed to be treatable by chiropractic include tension headaches and neck pain. Some sources suggest that there is some evidence of efficacy of chiropractic treatment in TMD,[86] but the sources cited for these statements were case reports and a case series of only 9 participants. One review concluded 'inconclusive evidence in a favorable direction regarding mobilization and massage for TMD'.[87] Overall, although there is general agreement that chiropractic may be of comparable benefit to other manual therapies for lower back pain, there is no credible evidence of efficacy in other conditions, including TMD.[88] However, there is some evidence of possible adverse effects from cervical (neck) vertebral manipulation, which sometimes may be serious.[88]

Prognosis[edit]

It has been suggested that the natural history of TMD is benign and self-limiting,[25] with symptoms slowly improving and resolving over time.[14] The prognosis is therefore good.[18] However, the persistent pain symptoms, psychological discomfort, physical disability and functional limitations may detriment quality of life.[89] It has been suggested that TMD does not cause permanent damage and does not progress to arthritis in later life,[25]:174–175 however degenerative disorders of the TMJ such as osteoarthritis are included within the spectrum of TMDs in some classifications.

Epidemiology[edit]

TMD mostly affects people in the 20 – 40 age group,[7] and the average age is 33.9 years.[9] People with TMD tend to be younger adults,[18] who are otherwise healthy. Within the catchall umbrella of TMD, there are peaks for disc displacements at age 30, and for inflammatory-degenerative joint disorders at age 50.[10]

About 75% of the general population may have at least one abnormal sign associated with the TMJ (e.g. clicking), and about 33% have at least one symptom of TMD.[24] However, only in 3.6–7% will this be of sufficient severity to trigger the individual to seek medical advice.[24]

For unknown reasons, females are more likely to be affected than males, in a ratio of about 2:1,[9] although others report this ratio to be as high as 9:1.[24] Females are more likely to request treatment for TMD, and their symptoms are less likely to resolve.[24] Females with TMD are more likely to be nulliparous than females without TMD.[5] It has also been reported that female caucasians are more likely to be affected by TMD, and at an earlier age, than female African Americans.[18]

According to the most recent analyses of epidemiologic data using the RDC/TMD diagnostic criteria, of all TMD cases, group I (muscle disorders) accounts for 45.3%, group II (disc displacements) 41.1%, and group III (joint disorders) 30.1% (individuals may have diagnoses from more than one group).[10] Using the RDC/TMD criteria, TMD has a prevelence in the general population of 9.7% for group I, 11.4% for group IIa, and 2.6% for group IIIa.[10]

History[edit]

Temporomandibular disorders were described as early as ancient Egypt.[24] An older name for the condition is 'Costen's syndrome', eponymously referring to James B. Costen.[90][91] Costen was an otolaryngologist,[92] and although he was not the first physician to describe TMD, he wrote extensively on the topic, starting in 1934, and was the first to approach the disorder in an integrated and systematic way.[93] Costen hypothesized that malocclusion caused TMD, and placed emphasis on ear symptoms, such as tinnitus, otaglia, impaired hearing, and even dizziness.[93] Specifically, Costen believed that the cause of TMD was mandibular over-closure,[92] recommending a treatment revolving around building up the bite.[92] The eponym 'Costen syndrome' became commonly used shortly after his initial work,[93] but in modern times it has been dropped, partially because occlusal factors are now thought to play little, if any, role in the development of TMD,[18] and also because ear problems are now thought to be less associated with TMD. Other historically important terms that were used for TMD include 'TMJ disease' or 'TMJ syndrome', which are now rarely used.[18]

References[edit]

- ^TMJ Disorders, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research

- ^ abcdefghijkMujakperuo HR, Watson M, Morrison R, Macfarlane TV (October 2010). 'Pharmacological interventions for pain in patients with temporomandibular disorders'. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (10): CD004715. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004715.pub2. PMID20927737.

- ^ abShi Z, Guo C, Awad M (2003). 'Hyaluronate for temporomandibular joint disorders'. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD002970. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002970. PMID12535445. (Retracted, see doi:10.1002/14651858.cd002970.pub2. If this is an intentional citation to a retracted paper, please replace

{{Retracted}}with{{Retracted intentional=yes}}.) - ^ abcdefghAl-Ani MZ, Davies SJ, Gray RJ, Sloan P, Glenny AM (2004). 'Stabilisation splint therapy for temporomandibular pain dysfunction syndrome'. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD002778. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002778.pub2. PMID14973990. (Retracted, see doi:10.1002/14651858.cd002778.pub3. If this is an intentional citation to a retracted paper, please replace

{{Retracted}}with{{Retracted intentional=yes}}.) - ^ abcdefghijklmnopqrstScully C (2008). Oral and maxillofacial medicine : the basis of diagnosis and treatment (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 8, 14, 30, 31, 33, 101, 104, 106, 291–295, 338, 339, 351. ISBN9780443068188.[page needed]

- ^ abcdefghijkCairns BE (May 2010). 'Pathophysiology of TMD pain--basic mechanisms and their implications for pharmacotherapy'. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation. 37 (6): 391–410. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2842.2010.02074.x. PMID20337865.

- ^ abcdGuo C, Shi Z, Revington P (October 2009). 'Arthrocentesis and lavage for treating temporomandibular joint disorders'. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD004973. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004973.pub2. PMID19821335. (Retracted, see doi:10.1002/14651858.cd004973.pub3. If this is an intentional citation to a retracted paper, please replace

{{Retracted}}with{{Retracted intentional=yes}}.) - ^ ab'Management of Temporomandibular Disorders. National Institutes of Health Technology Assessment Conference Statement'(PDF). 1996. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ^ abcdeEdwab RR, ed. (2003). Essential dental handbook : clinical and practice management advice from the experts. Tulsa, OK: PennWell. pp. 251–309. ISBN978-0-87814-624-6.

- ^ abcdefgManfredini D, Guarda-Nardini L, Winocur E, Piccotti F, Ahlberg J, Lobbezoo F (October 2011). 'Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review of axis I epidemiologic findings'(PDF). Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontics. 112 (4): 453–62. doi:10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.04.021. PMID21835653.

- ^ abcdeNeville BW, Damm DD, Allen CA, Bouquot JE (2002). Oral & maxillofacial pathology (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. pp. 75–9. ISBN978-0-7216-9003-2.

- ^ abAggarwal VR, Lovell K, Peters S, Javidi H, Joughin A, Goldthorpe J (November 2011). 'Psychosocial interventions for the management of chronic orofacial pain'. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (11): CD008456. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008456.pub2. PMID22071849. (Retracted, see doi:10.1002/14651858.cd008456.pub3. If this is an intentional citation to a retracted paper, please replace

{{Retracted}}with{{Retracted intentional=yes}}.) - ^ abcdefgFernandez CE, Amiri A, Jaime J, Delaney P (December 2009). 'The relationship of whiplash injury and temporomandibular disorders: a narrative literature review'. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine. 8 (4): 171–86. doi:10.1016/j.jcm.2009.07.006. PMC2786231. PMID19948308.

- ^ abc'Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD) Policy Statement'. American Association for Dental Research. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ abcdefgLuther F, Layton S, McDonald F (July 2010). McDonald F (ed.). 'Orthodontics for treating temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders'. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (7): CD006541. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006541.pub2. PMID20614447. (Retracted, see doi:10.1002/14651858.cd006541.pub3. If this is an intentional citation to a retracted paper, please replace

{{Retracted}}with{{Retracted intentional=yes}}.) - ^ abcdefghKindler LL, Bennett RM, Jones KD (March 2011). 'Central sensitivity syndromes: mounting pathophysiologic evidence to link fibromyalgia with other common chronic pain disorders'. Pain Management Nursing. 12 (1): 15–24. doi:10.1016/j.pmn.2009.10.003. PMC3052797. PMID21349445.

- ^ abcdefghijklmnopqrsWassell R, Naru A, Steele J, Nohl F (2008). Applied occlusion. London: Quintessence. pp. 73–84. ISBN978-1-85097-098-9.

- ^ abcdefghiJoseph Rios (22 February 2017). Robert A. Egan (ed.). 'Temporomandibular Disorders'. Medscape. WebMD. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ^ abcdefg'Classification of Chronic Pain, Part II, B. Relatively Localized Syndromes of the Head and Neck; Group III: Craniofacial pain of musculoskeletal origin'. IASP. Archived from the original on 19 December 2012. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ ab'2nd Edition International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-2)'. International Headache Society. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^'International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision'. World Health Organization. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ^ abcdefgOkeson JP (2003). Management of temporomandibular disorders and occlusion (5th ed.). St. Louis, Missouri: Mosby. pp. 191, 204, 233, 234, 227. ISBN978-0-323-01477-9.

- ^Armijo-Olivo, Susan; Pitance, Laurent; Singh, Vandana; Neto, Francisco; Thie, Norman; Michelotti, Ambra (2016). 'Effectiveness of Manual Therapy and Therapeutic Exercise for Temporomandibular Disorders: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis'. Physical Therapy. 96 (1): 9–25. doi:10.2522/ptj.20140548. ISSN0031-9023. PMC4706597. PMID26294683.

- ^ abcdefWright EF (2013). Manual of temporomandibular disorders (3rd ed.). Ames, IA: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 1–15. ISBN978-1-118-50269-3.

- ^ abcdefgCawson RA, Odell EW, Porter S (2002). Cawsonś essentials of oral pathology and oral medicine (7th ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN978-0-443-07106-5.[page needed]

- ^ abcdefGreenberg MS, Glick M (2003). Burket's oral medicine diagnosis & treatment (10th ed.). Hamilton, Ont: BC Decker. ISBN978-1-55009-186-1.[page needed]

- ^'Definitions of 'Arthrosis' from various medical and popular dictionaries'. Farlex. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ^ abcdefghOrlando B, Manfredini D, Salvetti G, Bosco M (2007). 'Evaluation of the effectiveness of biobehavioral therapy in the treatment of temporomandibular disorders: a literature review'. Behavioral Medicine. 33 (3): 101–18. doi:10.3200/BMED.33.3.101-118. PMID18055333.

- ^Tyldesley WR, Field A, Longman L (2003). Tyldesley's Oral medicine (5th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0192631473.[page needed]

- ^ abcdShetty S, Pitti V, Satish Babu CL, Surendra Kumar GP, Deepthi BC (September 2010). 'Bruxism: a literature review'. Journal of Indian Prosthodontic Society. 10 (3): 141–8. doi:10.1007/s13191-011-0041-5. PMC3081266. PMID21886404.

- ^De Meyer MD, De Boever JA (1997). '[The role of bruxism in the appearance of temporomandibular joint disorders]'. Revue Belge de Médecine Dentaire. 52 (4): 124–38. PMID9709800.

- ^Manfredini D, Lobbezoo F (June 2010). 'Relationship between bruxism and temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review of literature from 1998 to 2008'. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontics. 109 (6): e26–50. doi:10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.02.013. PMID20451831.

- ^Buescher JJ (November 2007). 'Temporomandibular joint disorders'. American Family Physician. 76 (10): 1477–82. PMID18052012.

- ^ abcdefghKerawala C, Newlands C, eds. (2010). Oral and maxillofacial surgery. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 342–351. ISBN9780199204830.

- ^Trovato F, Orlando B, Bosco M (2009). 'Occlusal features and masticatory muscles activity. A review of electromyographic studies'. Stomatologija. 11 (1): 26–31. PMID19423968.

- ^ abcKoh H, Robinson PG (April 2004). 'Occlusal adjustment for treating and preventing temporomandibular joint disorders'. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation. 31 (4): 287–92. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2842.2003.01257.x. PMID15089931.

- ^https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0013523/[full citation needed]

- ^Miller JR, Burgess JA, Critchlow CW (2004). 'Association between mandibular retrognathia and TMJ disorders in adult females'. Journal of Public Health Dentistry. 64 (3): 157–63. doi:10.1111/j.1752-7325.2004.tb02746.x. PMID15341139.

- ^Zadik Y, Drucker S (September 2011). 'Diving dentistry: a review of the dental implications of scuba diving'. Australian Dental Journal. 56 (3): 265–71. doi:10.1111/j.1834-7819.2011.01340.x. PMID21884141.

- ^Alomar X, Medrano J, Cabratosa J, Clavero JA, Lorente M, Serra I, Monill JM, Salvador A (June 2007). 'Anatomy of the temporomandibular joint'. Seminars in Ultrasound, CT, and MR. 28 (3): 170–83. doi:10.1053/j.sult.2007.02.002. PMID17571700.

- ^ abcStandring S, ed. (2006). Gray's anatomy : the anatomical basis of clinical practice (39th ed.). Edinburgh: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone. ISBN978-0-443-07168-3.

- ^Davies S, Gray RM (September 2001). 'What is occlusion?'. British Dental Journal. 191 (5): 235–8, 241–5. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.4801151a. PMID11575759.

- ^Westesson PL, Otonari-Yamamoto M, Sano T, Okano T (2011). 'Anatomy, Pathology, and Imaging of the Temporomandibular Joint'. In Som PM, Curtin HD (eds.). Head and neck imaging (5th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby Elsevier. ISBN978-0-323-05355-6.

- ^ abcCuccia AM, Caradonna C, Caradonna D (February 2011). 'Manual therapy of the mandibular accessory ligaments for the management of temporomandibular joint disorders'. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 111 (2): 102–12. PMID21357496.

- ^Odell EW, ed. (2010). Clinical problem solving in dentistry (3rd ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 37–41. ISBN9780443067846.

- ^Contemporary Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery fifth edition; Hupp, ellis, and tucker. 2008

- ^Ramírez LM, Sandoval GP, Ballesteros LE (April 2005). 'Temporomandibular disorders: referred cranio-cervico-facial clinic'(PDF). Medicina Oral, Patologia Oral y Cirugia Bucal. 10 (Suppl 1): E18–26. PMID15800464.

- ^Quail G (August 2005). 'Atypical facial pain--a diagnostic challenge'(PDF). Australian Family Physician. 34 (8): 641–5. PMID16113700.

- ^ abcdefghHupp JR, Ellis E, Tucker MR (2008). Contemporary oral and maxillofacial surgery (5th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier. pp. 629–47. ISBN978-0-323-04903-0.

- ^Zhang S, Gersdorff N, Frahm J (2011). 'Real-time magnetic resonance imaging of temporomandibular joint dynamics'(PDF). The Open Medical Imaging Journal. 5: 1–9. doi:10.2174/1874347101105010001.

- ^Anderson GC, Gonzalez YM, Ohrbach R, Truelove EL, Sommers E, Look JO, Schiffman EL (Winter 2010). 'The Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders. VI: future directions'. Journal of Orofacial Pain. 24 (1): 79–88. PMC3157036. PMID20213033.

- ^ abcdLimchaichana N, Petersson A, Rohlin M (October 2006). 'The efficacy of magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of degenerative and inflammatory temporomandibular joint disorders: a systematic literature review'. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontics. 102 (4): 521–36. doi:10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.02.001. PMID16997121.

- ^ abcHussain AM, Packota G, Major PW, Flores-Mir C (February 2008). 'Role of different imaging modalities in assessment of temporomandibular joint erosions and osteophytes: a systematic review'. Dento Maxillo Facial Radiology. 37 (2): 63–71. doi:10.1259/dmfr/16932758. PMID18239033.

- ^Wiese M, Wenzel A, Hintze H, Petersson A, Knutsson K, Bakke M, List T, Svensson P (August 2008). 'Osseous changes and condyle position in TMJ tomograms: impact of RDC/TMD clinical diagnoses on agreement between expected and actual findings'. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontics. 106 (2): e52–63. doi:10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.03.021. PMID18547834.

- ^Petersson A (October 2010). 'What you can and cannot see in TMJ imaging--an overview related to the RDC/TMD diagnostic system'. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation. 37 (10): 771–8. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2842.2010.02108.x. PMID20492436.

- ^ abcdeFerreira LA, Grossmann E, Januzzi E, de Paula MV, Carvalho AC (May 2016). 'Diagnosis of temporomandibular joint disorders: indication of imaging exams'. Brazilian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology. 82 (3): 341–52. doi:10.1016/j.bjorl.2015.06.010. PMID26832630.

- ^ abcdKlatkiewicz T, Gawriołek K, Pobudek Radzikowska M, Czajka-Jakubowska A (February 2018). 'Ultrasonography in the Diagnosis of Temporomandibular Disorders: A Meta-Analysis'. Medical Science Monitor. 24: 812–817. doi:10.12659/MSM.908810. PMC5813878. PMID29420457.

- ^Al-Saleh MA, Alsufyani NA, Saltaji H, Jaremko JL, Major PW (May 2016). 'MRI and CBCT image registration of temporomandibular joint: a systematic review'. Journal of Otolaryngology - Head & Neck Surgery = le Journal d'Oto-Rhino-Laryngologie et de Chirurgie Cervico-Faciale. 45 (1): 30. doi:10.1186/s40463-016-0144-4. PMC4863319. PMID27164975.

- ^Hintze H, Wiese M, Wenzel A (May 2007). 'Cone beam CT and conventional tomography for the detection of morphological temporomandibular joint changes'. Dento Maxillo Facial Radiology. 36 (4): 192–7. doi:10.1259/dmfr/25523853. PMID17536085.

- ^ abAlkhader M, Ohbayashi N, Tetsumura A, Nakamura S, Okochi K, Momin MA, Kurabayashi T (July 2010). 'Diagnostic performance of magnetic resonance imaging for detecting osseous abnormalities of the temporomandibular joint and its correlation with cone beam computed tomography'. Dento Maxillo Facial Radiology. 39 (5): 270–6. doi:10.1259/dmfr/25151578. PMC3520245. PMID20587650.

- ^ abcHunter A, Kalathingal S (July 2013). 'Diagnostic imaging for temporomandibular disorders and orofacial pain'. Dental Clinics of North America. 57 (3): 405–18. doi:10.1016/j.cden.2013.04.008. PMID23809300.

- ^ abcLewis EL, Dolwick MF, Abramowicz S, Reeder SL (October 2008). 'Contemporary imaging of the temporomandibular joint'. Dental Clinics of North America. 52 (4): 875–90, viii. doi:10.1016/j.cden.2008.06.001. PMID18805233.

- ^ abLandes CA, Goral WA, Sader R, Mack MG (May 2006). '3-D sonography for diagnosis of disk dislocation of the temporomandibular joint compared with MRI'. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 32 (5): 633–9. doi:10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.02.1401. PMID16677922.

- ^ abcdJank S, Zangerl A, Kloss FR, Laimer K, Missmann M, Schroeder D, Mur E (January 2011). 'High resolution ultrasound investigation of the temporomandibular joint in patients with chronic polyarthritis'. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 40 (1): 45–9. doi:10.1016/j.ijom.2010.09.001. PMID20961737.

- ^ abcBas B, Yılmaz N, Gökce E, Akan H (July 2011). 'Ultrasound assessment of increased capsular width in temporomandibular joint internal derangements: relationship with joint pain and magnetic resonance grading of joint effusion'. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontics. 112 (1): 112–7. doi:10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.02.020. PMID21543241.